Prevention of bladder cancer:

Although there’s no guaranteed way to prevent bladder cancer, you can take steps to help reduce your risk. For instance:

- Don’t smoke. If you don’t smoke, don’t start. If you smoke, talk to your doctor about a plan to help you stop. Support groups, medications and other methods may help you quit.

- Take caution around chemicals. If you work with chemicals, follow all safety instructions to avoid exposure.

- Choose a variety of fruits and vegetables. Choose a diet rich in a variety of colorful fruits and vegetables. The antioxidants in fruits and vegetables may help reduce your risk of cancer.

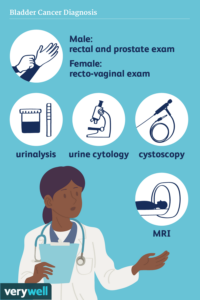

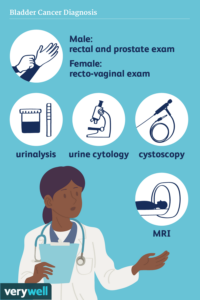

How bladder cancer is diagnosed could include the following:

- Using a scope to examine the inside of your bladder (cystoscopy). To perform cystoscopy, your doctor inserts a small, narrow tube (cystoscope) through your urethra. The cystoscope has a lens that allows your doctor to see the inside of your urethra and bladder, to examine these structures for signs of disease. Cystoscopy can be done in a doctor’s office or in the hospital.

- Removing a sample of tissue for testing (biopsy). During cystoscopy, your doctor may pass a special tool through the scope and into your bladder to collect a cell sample (biopsy) for testing. This procedure is sometimes called transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT). TURBT can also be used to treat bladder cancer.

- Examining a urine sample (urine cytology). A sample of your urine is analyzed under a microscope to check for cancer cells in a procedure called urine cytology.

- Imaging tests. Imaging tests, such as computerized tomography (CT) urogram or retrograde pyelogram, allow your doctor to examine the structures of your urinary tract.During a CT urogram, a contrast dye injected into a vein in your hand eventually flows into your kidneys, ureters and bladder. X-ray images taken during the test provide a detailed view of your urinary tract and help your doctor identify any areas that might be cancer.Retrograde pyelogram is an X-ray exam used to get a detailed look at the upper urinary tract. During this test, your doctor threads a thin tube (catheter) through your urethra and into your bladder to inject contrast dye into your ureters. The dye then flows into your kidneys while X-ray images are captured.

Determining the extent of the cancer

After confirming that you have bladder cancer, your doctor may recommend additional tests to determine whether your cancer has spread to your lymph nodes or to other areas of your body.

Tests may include:

- CT scan

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- Positron emission tomography (PET)

- Bone scan

- Chest X-ray

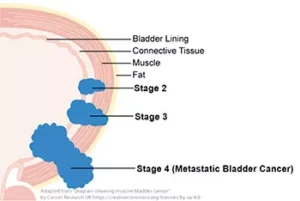

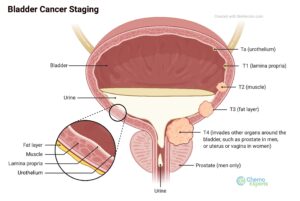

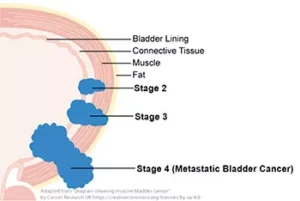

Staging of Bladder Cancer:

Your doctor uses these diagnostic tests listed above for information from these procedures to assign your cancer a stage.

The stages of bladder cancer are indicated by Roman numerals ranging from 0 to IV. The lowest stages indicate a cancer that’s confined to the inner layers of the bladder and that hasn’t grown to affect the muscular bladder wall. The highest stage — stage IV — indicates cancer that has spread to lymph nodes or organs in distant areas of the body, like a lot of other cancers are staged I through IV.

Treatments of bladder cancer:

If cancer invades the muscles of the bladder, doctors will usually treat it with chemotherapy to shrink the tumor, followed by surgery to remove the bladder. However, a recent clinical trial found that adding immunotherapy to chemotherapy may allow certain patients to avoid surgery.

Bladder cancer treatment may include: Surgery, to remove the cancer cells. Chemotherapy in the bladder (intravesical chemotherapy), to treat cancers that are confined to the lining of the bladder but have a high risk of recurrence or progression to a higher stage.

Approaches to bladder cancer surgery might be used could include:

- Transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT). TURBT is a procedure to diagnose bladder cancer and to remove cancers confined to the inner layers of the bladder — those that aren’t yet muscle-invasive cancers. During the procedure, a surgeon passes an electric wire loop through a cystoscope and into the bladder. The electric current in the wire is used to cut away or burn away the cancer. Alternatively, a high-energy laser may be used.Because doctors perform the procedure through the urethra, you won’t have any cuts (incisions) in your abdomen.As part of the TURBT procedure, your doctor may recommend a one-time injection of cancer-killing medication (chemotherapy) into your bladder to destroy any remaining cancer cells and to prevent cancer from coming back. The medication remains in your bladder for a period of time and then is drained.

- Cystectomy. Cystectomy is surgery to remove all or part of the bladder. During a partial cystectomy, your surgeon removes only the portion of the bladder that contains a single cancerous tumor.A radical cystectomy is an operation to remove the entire bladder and the surrounding lymph nodes. In men, radical cystectomy typically includes removal of the prostate and seminal vesicles. In women, radical cystectomy may involve removal of the uterus, ovaries and part of the vagina.Radical cystectomy can be performed through an incision on the lower portion of the belly or with multiple small incisions using robotic surgery. During robotic surgery, the surgeon sits at a nearby console and uses hand controls to precisely move robotic surgical instruments.

- Neobladder reconstruction. After a radical cystectomy, your surgeon must create a new way for urine to leave your body (urinary diversion). One option for urinary diversion is neobladder reconstruction. Your surgeon creates a sphere-shaped reservoir out of a piece of your intestine. This reservoir, often called a neobladder, sits inside your body and is attached to your urethra. The neobladder allows most people to urinate normally. A small number of people difficulty emptying the neobladder and may need to use a catheter periodically to drain all the urine from the neobladder.

- Ileal conduit. For this type of urinary diversion, your surgeon creates a tube (ileal conduit) using a piece of your intestine. The tube runs from your ureters, which drain your kidneys, to the outside of your body, where urine empties into a pouch (urostomy bag) you wear on your abdomen.

- Continent urinary reservoir. During this type of urinary diversion procedure, your surgeon uses a section of intestine to create a small pouch (reservoir) to hold urine, located inside your body. You drain urine from the reservoir through an opening in your abdomen using a catheter a few times each day.

Chemotherapy drugs can be given:

- 1-Through a vein (intravenously). Intravenous chemotherapy is frequently used before bladder removal surgery to increase the chances of curing the cancer. Chemotherapy is going in your system generally through the blood stream and chemo may also be used to kill cancer cells that might remain after surgery. In certain situations, chemotherapy may be combined with radiation therapy.

- 2-Directly into the bladder (intravesical therapy). During intravesical chemotherapy, a tube is passed through your urethra directly to your bladder. The chemotherapy is placed in the bladder for a set period of time before being drained. It can be used as the primary treatment for superficial bladder cancer, where the cancer cells affect only the lining of the bladder and not the deeper muscle tissue.

Radiation therapy:

Radiation therapy uses beams of powerful energy, such as X-rays and protons, to destroy the cancer cells. Radiation therapy for bladder cancer usually is delivered from a machine that moves around your body, directing the energy beams to precise points.

Radiation therapy is sometimes combined with chemotherapy to treat bladder cancer in certain situations, such as when surgery isn’t an option or isn’t desired at that time or ever depending on your stage of cancer.

Immunotherapy:

Immunotherapy is a drug treatment that helps your immune system to fight cancer.

Immunotherapy can be given:

- Directly into the bladder (intravesical therapy). Intravesical immunotherapy might be recommended after TURBT for small bladder cancers that haven’t grown into the deeper muscle layers of the bladder. This treatment uses bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG), which was developed as a vaccine used to protect against tuberculosis. BCG causes an immune system reaction that directs germ-fighting cells to the bladder.

- Through a vein (intravenously). Immunotherapy can be given intravenously for bladder cancer that’s advanced or that comes back after initial treatment. Several immunotherapy drugs are available. These drugs help your immune system identify and fight the cancer cells.

Targeted therapy:

Targeted therapy drugs focus on specific weaknesses present within cancer cells. By targeting these weaknesses, targeted drug treatments can cause cancer cells to die. Your cancer cells may be tested to see if targeted therapy is likely to be effective.

Targeted therapy may be an option for treating advanced bladder cancer when other treatments haven’t helped.

Bladder preservation:

In certain situations, people with muscle-invasive bladder cancer who don’t want to undergo surgery to remove the bladder may consider trying a combination of treatments instead. Known as trimodality therapy, this approach combines TURBT, chemotherapy and radiation therapy.

First, your surgeon performs a TURBT procedure to remove as much of the cancer as possible from your bladder while preserving bladder function. After TURBT, you undergo a regimen of chemotherapy along with radiation therapy.

If, after trying trimodality therapy, not all of the cancer is gone or you have a recurrence of muscle-invasive cancer, your doctor may recommend a radical cystectomy.

After bladder cancer treatment:

Bladder cancer may recur, even after successful treatment. Because of this, people with bladder cancer need follow-up testing for years after successful treatment. What tests you’ll have and how often depends on your type of bladder cancer and how it was treated, among other factors.

In general, doctors recommend a test to examine the inside of your urethra and bladder (cystoscopy) every three to six months for the first few years after bladder cancer treatment. After a few years of surveillance without detecting cancer recurrence, you may need a cystoscopy exam only once a year. Your doctor may recommend other tests at regular intervals as well.

People with aggressive cancers may undergo more-frequent testing. Those with less aggressive cancers may undergo testing less often.