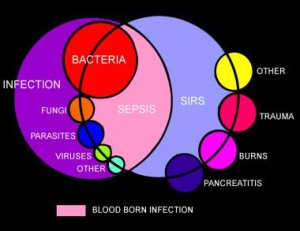

Part 3 talks to you about the multi-hit theory of SIRS with Inflammatory Cascade of SIRS and lastly the coagulation process in SIRS. It also tells you an extensive amount of infectious and non-infectious causes of SIRS. Lastly the key antidote to SIRS.

Multi-hit theory

A multi hit theory behind the progression of SIRS to organ dysfunction and possibly multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS). In this theory, the event that initiates the SIRS cascade primes the pump. With each additional event, an altered or exaggerated response occurs, leading to progressive illness. The key to preventing the multiple hits is adequate identification of the ETIOLOGY or CAUSE of SIRS and appropriate resuscitation and therapy.

Inflammatory cascade

Trauma, inflammation, or infection leads to the activation of the inflammatory cascade. Initially, a pro-inflammatory activation occurs, but almost immediately thereafter a reactive suppressing anti-inflammatory response occurs. This SIRS usually manifests itself as increased systemic expression of both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory species. When SIRS is mediated by an infectious insult, the inflammatory cascade is often initiated by endotoxin or exotoxin. Tissue macrophages, monocytes, mast cells, platelets, and endothelial cells are able to produce a multitude of cytokines. The cytokines tissue necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-1 (IL-1) are released first and initiate several cascades.

The release of certain factors without getting into medical specific terms they ending line induces the production of other pro-inflammatory cytokines, worsening the condition.

Some of these factors are the primary pro-inflammatory mediators. In research it suggests that glucocorticoids may function by inhibit-ing certain factors that have been shown to be released in large quantities within 1 hour of an insult and have both local and systemic effects. In studies they have shown that certain cytokines given individually produce no significant hemodynamic response but that they cause severe lung injury and hypotension. Others responsible for fever and the release of stress hormones (norepinephrine, vasopressin, activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system).

Other cytokines, stimulate the release of acute-phase reactants such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and pro-calcitonin.

The pro-inflammatory interleukins either function directly on tissue or work via secondary mediators to activate the coagulation cascade and the complement cascade and the release of nitric oxide, platelet-activating factor, prostaglandins, and leukotrienes.

High mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) is a protein present in the cytoplasm and nuclei in a majority of cell types. In response to infection or injury, as is seen with SIRS, HMGB1 is secreted by innate immune cells and/or released passively by damaged cells. Thus, elevated serum and tissue levels of HMGB1 would result from many of the causes of SIRS.

HMGB1 acts as a potent pro-inflammatory cytokine and is involved in delayed endotoxin lethality and sepsis.

Numerous pro-inflammatory polypeptides are found within the complement cascade. It is thought they are felt to contribute directly to the release of additional cytokines and to cause vasodilatation and increasing vascular permeability. Prostaglandins and leukotrienes incite endothelial damage, leading to multi-organ failure.

Polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs) from critically ill patients with SIRS have been shown to be more resistant to activation than PMNs from healthy donors, but, when stimulated, demonstrate an exaggerated micro-bicidal response (agents that kill microbes). This may represent an auto-protective mechanism in which the PMNs in the already inflamed host may avoid excessive inflammation, thus reducing the risk of further host cell injury and death.[4]

Coagulation

The correlation between inflammation and coagulation is critical to understanding the potential progression of SIRS. IL-1 and TNF-α directly affect endothelial surfaces, leading to the expression of tissue factor. Tissue factor initiates the production of thrombin, thereby promoting coagulation, and is a proinflammatory mediator itself. Fibrinolysis is impaired by IL-1 and TNF-α via production of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1. Pro-inflammatory cytokines also disrupt the naturally occurring anti-inflammatory mediators anti-thrombin and activated protein-C (APC).

If unchecked, this coagulation cascade leads to complications of micro-vascular thrombosis, including organ dysfunction. The complement system also plays a role in the coagulation cascade. Infection-related pro-coagulant activity is generally more severe than that produced by trauma.

What the causes of SIRS can be:

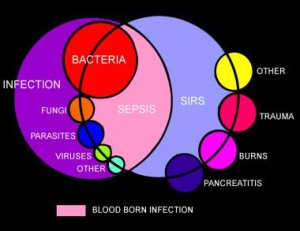

The etiology of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) is broad and includes infectious and noninfectious conditions, surgical procedures, trauma, medications, and therapies.

The following is partial list of the infectious causes of SIRS:

- Bacterial sepsis

- Burn wound infections

- Candidiasis

- Cellulitis

- Cholecystitis

- Community-acquired pneumonia [5]

- Diabetic foot infection

- Erysipelas

- Infective endocarditis

- Influenza

- Intra-abdominal infections (eg, diverticulitis, appendicitis)

- Gas gangrene

- Meningitis

- Nosocomial pneumonia

- Pseudomembranous colitis

- Pyelonephritis

- Septic arthritis

- Toxic shock syndrome

- Urinary tract infections (male and female)

- The following is a partial list of the noninfectious causes of SIRS:

- Acute mesenteric ischemia

- Adrenal insufficiency

- Autoimmune disorders

- Burns

- Chemical aspiration

- Cirrhosis

- Cutaneous vasculitis

- Dehydration

- Drug reaction

- Electrical injuries

- Erythema multiforme

- Hemorrhagic shock

- Hematologic malignancy

- Intestinal perforation

- Medication side effect (eg, from theophylline)

- Myocardial infarction

- Pancreatitis [6]

- Seizure

- Substance abuse – Stimulants such as cocaine and amphetamines

- Surgical procedures

- Toxic epidermal necrolysis

- Transfusion reactions

- Upper gastrointestinal bleeding

- VasculitisThe treatment is don’t get it since it is hard to get rid of especially for people over 65 and in hospitals. There is no one Rx for it. If you’re unfortunate enough to be diagnosed with SIRS the sooner you get diagnosed with it including being in stage one as opposed to three the higher the odds the turn out will be for you. Again the key is prevention; don’t get it. There is no one antidote to this SIRS.

- QUOTE FOR THIS ARTICLE:

- PREVENTION IS THE KEY ANTIDOTE! So stay healthy and out of hospitals!

“SIRS can be incited by ischemia, inflammation, trauma, infection or a combination of several “insults”. SIRS is not always associated with infection. While not universally accepted, some have proposed the terms “severe SIRS” and “SIRS shock” to describe serious clinical syndromes that are not infectious in nature and thus cannot be labeled according to the various sepsis definitions”

Steven D. Burdette M.D. (Infectious Disease Medicine M.D.– Wright State Physicians in Dayton, Ohio – http://www.healthgrades.com/physician/dr-steven-burdette-yhfgy)