Most Recent Mosquito Virus: Zika Virus

Background in health crisis response and that we have known about this for sometime now.

From January 2015 to October 2018, 5,442 travel-associated cases of Zika and 231 locally transmitted cases had been reported in the U.S., according to the CDC.

AmeriCares Zika response leverages the technical expertise of our health experts and our more than 30 years of experience with international health crises. AmeriCares has responded to mosquito-borne disease outbreaks in the past, from West Nile in the United States to chikungunya in Latin America and the Caribbean. In 2014, during an outbreak of chikungunya, our response included support for a community health education campaign that reached more than 10,000 people in El Salvador through schools, sporting events and community centers.

The World Health Organization declared an international public health emergency on February 1 2016 because of a suspected link between the virus and microcephaly, a condition in which babies are born with unusually small heads and abnormal brain development. There is growing evidence of an association between the increase in babies born with microcephaly, other possible birth defects and the incidence of Guillain-Barré syndrome that coincided with Zika virus infections. Currently, 33 countries and territories in the Americas have reported Zika cases, with up to 1.5 million confirmed cases in Brazil alone. The WHO is anticipating 3 million to 4 million more Zika infections in the region in the next 12 months.

There is no cure for Zika, but clinicians can help patients manage symptoms, giving them medicine to reduce fever and pain. They can also provide education on how to protect their families from the mosquitos that carry the virus.

Where are we actually working:

In Haiti, AmeriCares is working with a partner organization on a prevention program for expectant mothers, with the goal of keeping the women Zika-free until they deliver. In El Salvador, AmeriCares is developing a Zika-prevention program at its clinic, which provides primary and specialty care services for more than 60,000 patients annually, including prenatal care.

AmeriCares, which donates medicine and supplies to U.S.-based medical teams volunteering overseas, is also providing education materials to medical professionals working in Zika-affected countries. AmeriCares is supporting more than 150 medical teams planning travel to Latin America and the Caribbean through June.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and what they say about this Zika Virus:

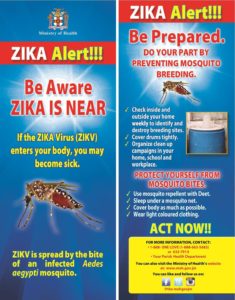

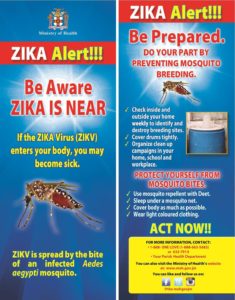

Zika virus disease (Zika) is a disease caused by Zika virus that is spread to people primarily through the bite of an infected Aedes species mosquito. The most common symptoms of Zika are fever, rash, joint pain, and conjunctivitis (red eyes). The illness is usually mild with symptoms lasting for several days to a week after being bitten by an infected mosquito. People usually don’t get sick enough to go to the hospital, and they very rarely die of Zika.

For this reason, many people might not realize they have been infected. Once a person has been infected, he or she is likely to be protected from future infections. Though being checked for it yearly might not hurt if your country is exposed to it and could easily spread; especially if you have family traveling in your country as well as those you travel to countries known to be at risk for this disease and should be check when returning to their country like the USA for example. It is called prevention and control by the government and health parties of that country; pretty common sense. Instead it appears till the USA and other countries just wait till damage occurs – an epidemic some areas reaching out for help if the country doesn’t have the funds for controlling the epidemic. Why not help out for education and research before the epidemic if the disease is already known.

Zika virus was first discovered in 1947 and is named after the Zika forest in Uganda. In 1952, the first human cases of Zika were detected and since then, outbreaks of Zika have been reported in tropical Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific Islands. Zika outbreaks have probably occurred in many locations. Before 2007, at least 14 cases of Zika had been documented, although other cases were likely to have occurred and were not reported. Because the symptoms of Zika are similar to those of many other diseases, many cases may not have been recognized.

In May 2015, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) issued an alert regarding the first confirmed Zika virus infection in Brazil and on Feb 1, 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared Zika virus a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) but not home prevention in the USA, like travelers from countries exposed with this that can be spread through a bite by a flying bug or possibly via sex so have the travelers returning checked to protect all in their country. Local transmission also has been reported in many other countries and territories. Zika virus likely will continue to spread to new areas. Let’s wake up and take action to control this from spreading in the USA and if possible other countries; especially our allies who travel here who are high with this virus treatment one day for this mosquito/sexual transmitted disease.

You’ve probably heard about Zika virus. But what is it exactly? Who is at risk? And what can you do to help?

Through PSIimpact.com has extensive experience helping families in the developing world overcome their most pressing health challenges. Here is what we know about Zika virus and how you can help.

- The Zika virus is carried by mosquitoes and people. Typically, mosquitoes spread the virus. But there is evidence the virus may be sexually transmitted from someone who has been infected to his sexual partner.

- The mosquitoes that carry Zika are active during the daytime, so malaria-fighting bed nets are not effective in stopping infection. Reducing breeding sites and using insecticides are currently two of the most effective ways to prevent the disease.

- Symptoms of Zika virus infection are usually mild, typically begin a few days after being bitten, and usually finish in 2 to 7 days. Eighty percent of people who become infected never have symptoms. In those who do, the most common are fever, rash and conjunctivitis.

- S. travelers are bringing the virus back with them. These imported cases happen when a person is infected elsewhere and then visits or returns to the United States.

- There’s no vaccine to protect against the Zika virus, but researchers are working on one. Once a person becomes infected with the virus they usually develop immunity to future infections.

- Researchers are studying the potential link between the Zika virus in pregnant women and microcephaly in their babies. Microcephaly is a birth defect that impairs brain development and can cause mild to severe cognitive delays, learning disabilities and impaired motor functions. The condition is marked by an abnormally small head.

- Until a link is confirmed, it is crucial that women who are pregnant strictly follow steps to prevent mosquito bites.

- The CDC recommends that pregnant women in any trimester consider postponing travel to the areas where Zika virus transmission is ongoing. The most recent travel advisories can be found on their website.

- Several Latin American countries have urged women not to get pregnant for up to two years if visiting those areas with this disease or from those Latin American area moving to another country like America included, in an attempt to avoid birth defects believed to be caused by Zika. However, no government has announced plans to increase access or remove barriers to contraception.

- PSI is already working in affected areas including El Salvador, Haiti, Honduras, Guatemala, the Dominican Republic and other countries in Latin America and the Caribbean. We are supporting national responses led by the Ministries of Health. And we will continue helping men and women access contraception so that they can make their own decision about when — and whether — to become pregnant. Thank you PSI for your knowledge and effort in researching