If one day you start the day going to work than come home feeling like a sinus infection that appears to be spreading to the ears and after going to bed several hours upon wakening I sat up on my bed finding yourself pulling to one side that you think the cause is an ear infection but it could be something else. When I was getting up and feeling dizzy but made it downstairs to eat a meal but due to the dizziness I vomited causing dizziness to increase terribly (like if sea sick or even like too much alcohol followed with vomiting and now everything’s spinning to the point you can’t get up from the ground) and got my self safely to the ground and couldn’t get up. This all happened to me one year and when going to the MD that night I was sent to the ER for being ruled out initially of a stroke or transient ischemic attack. I was aggravated and went. I than was finding out in the ERmit wasn’t a stroke or TIA, which is what I thought would be the result, but their still was a reason for it. What might this be? I was diagnosed with BPPV for severe dehydration and it took me a week through exercises and taking meclizine, also known as antivert, that took my dizziness away.

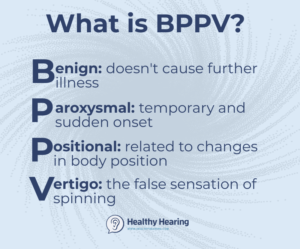

This could be an ear infection with BPPV or just BPPV itself; this abbreviation stands for BPPV-Benign Paroxsymal Posterior Vertigo (highly probable if its feeling clogged, no draining from the ear canal, no wax build up after checked with an otoscope by an ENT or Neurologist and the symptoms listed above present that I mentioned= Vertigo, Nausea; Possibly vision disturbance with lethargy) including a nystagmus (described below). This is how you feel after a concussion (with or without a nystagmus) in varying intensities depending on the impact after a blow to the head. How do these symptoms arise with no infection in the ear?

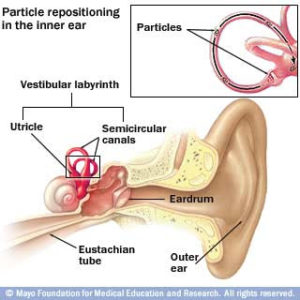

This involves the inner ear causing the brain to pick up miscommunication signals in detecting or reading what is happening going on giving the ending result of vertigo =dizziness, causing your balance to be off, which again I reenforce is due to the condition that is going on in the middle ear. It is the sensitivity detection by ear sensitivity hairs picking up what shouldn’t be there, which in turn is causing the symptoms. This can be due to inner ear particles clumped together in the ear or particles in the inner ear floating freely depending where the are located in the inner ear. We will discuss this more in detail shortly, just know these particles are called “rocks”.

If your having these symptoms this should be checked for BPPV and (I do recommend you go to MD to be evaluated first):

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is probably the most common cause of vertigo in the United States. It has been estimated that at least 20% of patients who present to the physician with vertigo have BPPV. However, because BPPV is frequently misdiagnosed, this figure may not be completely accurate and is probably an underestimation. Since BPPV can occur concomitantly with other inner ear diseases (for example, one patient may have both Ménière disease and BPPV at once), statistical analysis may be skewed toward lower numbers.

BPPV was first described by Barany in 1921. The characteristic nystagmus and vertigo associated with positioning changes were attributed at that time to the otolithic organs. In 1952, Dix and Hallpike performed the provocative positional testing named in their honor, shown below. They further defined classic nystagmus and went on to localize the pathology to the proper ear during provocation.

It deals with the inner ear.

The patient is placed in a sitting position with the head turned 45° towards the affected side and then reclined past the supine position.

BPPV is defined as an abnormal sensation of motion that is elicited by certain critical provocative positions. The provocative positions usually trigger specific eye movements (ie, nystagmus). The character and direction of the nystagmus are specific to the part of the inner ear affected and the pathophysiology.

BPPV is a complex disorder to define; because an evolution has occurred in the understanding of its pathophysiology, an evolution has also occurred in its definition. As more interest is focused on BPPV, new variations of positional vertigo have been discovered. What was previously grouped as BPPV is now subclassified by the offending semicircular canal (SCC; ie, posterior superior SCC vs lateral SCC) and, although controversial, further divided into canalithiasis and cupulolithiasis (depending on its pathophysiology).

Although some controversy exists regarding the 2 pathophysiologic mechanisms, canalithiasis and cupulolithiasis, agreement is growing that the entities actually coexist and account for different subspecies of BPPV. Canalithiasis (literally, “canal rocks”) is defined as the condition of particles residing in the canal portion of the SCCs (in contradistinction to the ampullary portion). These densities are considered to be free floating and mobile, causing vertigo by exerting a force. Conversely, cupulolithiasis (literally, “cupula rocks”) refers to densities adhered to the cupula of the crista ampullaris. Cupulolith particles reside in the ampulla of the SCCs and are not free floating.

Classic BPPV is the most common variety of BPPV. It involves the posterior SCC and is characterized by the following symptoms:

- Geotropic nystagmus with the problem ear down

- Predominantly rotatory fast phase toward undermost ear

- Latency (a few seconds)

- Limited duration (< 20 s)

- Reversal upon return to upright position

- Response decline upon repetitive provocation. The purpose for this appears to be the brain acquires a response in getting used to this vertigo as normal by picking up wrong messages from that affected ear due to improper messaging by the pick up of how the rocks in the inner ear canal are situated (free floating or residing in a canal portion with how the ear hairs are picking up by sensitivity their presence giving wrong messages to the brain causing vertigo, nystagmus, with or without vomiting.

- Because the type of BPPV is defined by the distinguishing type of nystagmus, defining and explaining the characterizing nystagmus are also important.

- Nystagmus is defined as involuntary eye movements usually triggered by inner ear stimulation. It usually begins as a slow pursuit movement followed by a fast, rapid resetting phase. Nystagmus is named by the direction of the fast phase. Thus, nystagmus may be termed right beating, left beating, up-beating (collectively horizontal), down-beating (vertical), or direction changing.

- If the movements are not purely horizontal or vertical, the nystagmus may be deemed rotational. In rotational nystagmus, the terminology becomes a bit more loose or unconventional. Terms such as clockwise and counterclockwise seem useful until discrepancies regarding point of view arise: clockwise to the patient is counterclockwise to the observer. Right versus left terminology is poorly descriptive because as the top half of the eye rotates right, the bottom half moves left.

- Rotational nystagmus also can be described as geotropic and ageotropic. Geotropic means “toward earth” and refers to the upper half of the eye. Ageotropic refers to the opposite movement. If the head is turned to the right, and the eye rotation is clockwise from the patient’s point of view (top half turns to the right and toward the ground), then the nystagmus is geotropic. If the head is turned toward the left, then geotropic nystagmus is a counterclockwise rotation. This term is particularly useful in describing BPPV nystagmus because the word geotropic remains appropriate whether the right or the left side is involved.

- These 2 terms are useful only when the head is turned. If the patient is supine and looking straight up, these terms cannot be used. Fortunately, the nystagmus associated with BPPV usually is provoked with the head turned to one side. The most accurate way to define nystagmus is by terming it clockwise or counterclockwise from the patient’s point of view.

The tympanic membrane where no doctor can open that and further the problem is in your semi-circular canal and if not resolving the problem it will damage the ear.