Ventilator Acquired Pneumonia

C-Diff

Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia

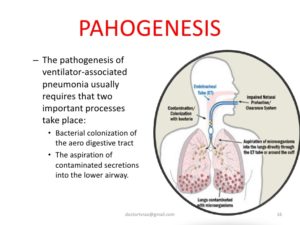

Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is an infection of the lungs that develops after a person has been on a ventilator for longer than 48 hours. The most common type of HAI contracted in the ICU, VAP occurs in as many as 28% of patients who have had mechanical ventilation. Infection occurs because the endotracheal or tracheostomy tube allows passage of microbes into the lungs. These organisms may originate from the patient’s aspirate, from the oropharynx and digestive tract, or from external sources, such as contaminated equipment and medications.

Although any microbe can be the causative agent, certain microbes are most often implicated due to increasing drug resistance. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is the most common multidrug-resistant organism responsible for VAP. Other microbes that cause VAP include Staphlococcus aureus, Klebsiella spp., Escherichia coli, Enterobacter spp., Actinobacter spp., MRSA, and Serratia marcescens. Pneumonia is considered early in onset if it occurs within the first 4 days after hospital admission. Multidrug resistant organisms are more likely to be the cause of late-onset pneumonia, defined as 5 or more days postadmission.

In addition to recent ventilation, other risk factors increase a patient’s chance of acquiring VAP, such as hospitalization or antibiotic use within the past 90 days, hospital stay greater than 5 days, hemodialysis within the past 30 days, and known circulation of multidrug-resistant organisms in the facility. Immunocompromised residents and those who reside in a nursing home or long-term care facility are also at greater risk for VAP.

Symptoms of VAP include fever, a decline in oxygenation, leukocytosis, and purulent sputum. Diagnosis of VAP is made based on comprehensive medical history, presence of infiltrates on x-ray, and positive culture of lower respiratory tract secretions (colonization of the trachea is common; thus a positive culture may not distinguish a pathogen from a colonizing organism). Symptoms of ventilator associated tracheobronchitis (VAT) with purulent secretions can mimic symptoms of VAP. VAT is a condition midway between colonization and VAP and requires antibiotic treatment.

Treatment should not be delayed while diagnostic tests are pending. Empiric treatment is vital in patients with suspected VAP and can be based on patient risk factors for multidrug-resistant organisms, known local prevalence of resistant organisms, severity of infection, and total number of days the patient was hospitalized before the onset of pneumonia. Criteria for empiric treatment include a new or progressive infiltrate on x-ray and at least two of the following conditions: fever greater than 38°C, leukocytosis or leukopenia, and purulent respiratory secretions.

If the patient has received recent doses of antibiotics, a different class of antibiotics should be used for treatment. Therapy should later be adjusted based on culture results. Unless diagnostic testing shows otherwise, initial empiric therapy should not be changed in the first 48 to 72 hours because clinical response to antibiotic therapy is not likely during this time frame. Patients should be treated with antibiotic therapy for at least 72 hours after a clinical response is attained. (For specific antibiotics and dosages, see the Infectious Disease Society of America practice guidelines for patient care at www.idsociety.org.)

To prevent VAP, the CDC recommends the following strategies:

Strategies to Prevent Aspiration

- Maintain patients in a semirecumbent position.

- Avoid gastric overdistention.

- Avoid unplanned extubation and reintubation.

- Use a cuffed endotracheal tube with inline or subglottic suctioning.

- Maintain an endotracheal cuff pressure of at least 20 cm water.

Strategies to Reduce Colonization of the Aerodigestive Tract

- When possible, use orotracheal intubation rather than nasotracheal intubation.

- Avoid histamine receptor 2 (H2)–blocking agents and proton pump inhibitors for patients who are not at high risk for developing a stress ulcer or stress gastritis.

- Perform regular oral care with an antiseptic solution.

Strategies to Minimize Contamination of Equipment

- Use sterile water to rinse reusable respiratory equipment.

- Remove condensate from ventilatory circuits, keeping the ventilatory circuit closed while you do so.

- Change the ventilatory circuit only when visibly soiled or malfunctioning.

- Store and disinfect respiratory therapy equipment properly.

In addition to these strategies, healthcare professionals should perform daily assessments of readiness to wean to minimize the duration of ventilation. Whenever possible, use noninvasive ventilation methods.

Clostridium difficile Infection

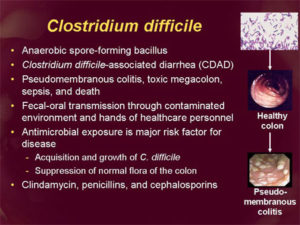

Clostridium difficile infection (CDI), or Clostridium difficile–associated disease (CDAD), is an infection of the intestines caused by the anaerobic, spore-forming, gram-positive bacillus C. difficile. (Figure 2)This microbe was first identified in 1935 when it was isolated from the stools of neonates. C. difficile produces heat-resistant spores that can remain viable on fomites in the environment for years, becoming a source of outbreaks in healthcare facilities. This bacillus also produces two types of toxins: Toxin A (an enterotoxin) and Toxin B (a cytotoxin). These toxins are responsible for the inflammatory responses of the colon, which results in loss of epithelial integrity and the production of watery diarrhea. C. difficile is the most common cause of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and pseudomembranous colitis and has proved extremely difficult to control due to new, more resistant strains.

C.difficile taken from a stool sample culture.

Source: CDC Public Health Image Library PHIL #9999, photo credit Janice Haney Carr, CDC.

- difficile is found in the intestinal tract of up to 70% of healthy infants, 1–3% of healthy adults, and in higher rates (up to 20%) in persons on antibiotic therapy. Prevalence, severity, colectomy rates, and mortality rates due to C. difficile have all risen in the past two decades, proving that this microbe has become an extremely virulent superbug that is both persistent and difficult to treat. Surveillance data from the CDC show that between 2000 and 2007 mortality from C. difficile increased by 400% due to a more virulent strain of this organism.

Studies of hospital-acquired CDI have shown that the infection is independently associated with increased risk of in-hospital death: For every 10 hospital patients who acquire a CDI, 1 patient died. Data from the CDC show that C. difficile is responsible for 337,000 infections and 14,000 deaths in the United States each year.

The greatest risk factor for CDI is the use of antibiotics, such as cephlasporins, clindamycin, or the penicillins, because these antibiotics kill the normal flora of the colon, causing overgrowth of C. difficile. Risk is increased for those taking multiple antimicrobials and those who take antimicrobials for longer time periods. Other risk factors for CDI include advanced age. Although almost half of the infections occur in persons younger than 65, most CDI-related deaths occur in the elderly. People with HIV infection, compromised immune systems, and compromised physical status are also at increased risk for CDI. Hospital admission increases one’s chance of acquiring CDI, as does gastrointestinal surgery.

Transmission of CDI occurs by the fecal-oral route.

The time between exposure to C. difficile and infection is 2 to 3 days.

Symptoms of CDI vary greatly, ranging from asymptomatic to mild (fever, malaise, and gastrointestinal symptoms, including abdominal pain and cramps, and mild to moderate foul-smelling diarrhea that is rarely bloody) to extremely severe toxic megacolon, septic shock, and even death. Complications of C. difficile include pseudomembranous colitis or fulminant colitis.

Diagnosis is based on clinical history (antibiotic use in the previous 2 months, diarrhea after 72 or more hours of hospitalization), and presence of C. difficile in the stool. Stool culture is the most sensitive test and is often used for diagnosis in the hospital setting. Colonoscopy revealing histopathology with pseudomembranous colitis is also diagnostic but not necessary in most cases.

Treatment for CDI begins with discontinuation of the antibiotic causing the infection. In many cases, this step is the only necessary treatment since normal flora can reestablish in the colon. If mild to moderate diarrhea persists, patients can be treated with either metronidazole or vancomycin. In cases of severe diarrhea, vancomycin is the drug of choice for treatment due to its history of rapid symptom resolution and overall fewer treatment failures. Although antibiotic treatment will clear the infection, it will not kill the bacterial spores. In 27% of cases, relapse occurs within 3 weeks of antibiotic termination. In extreme cases, colectomy with end ileostomy may be necessary. Treatment for asymptomatic cases is not recommended.

An innovative CDI treatment may be on the horizon. Researchers have shown that C. difficile infection arises as the result of the disruption of natural flora in the intestines, a condition known as dysbiosis. New research in the treatment of CDI involves isolating specific gut bacteria in the fecal matter of healthy individuals and incorporating it into the gut of a person with CDI to restore normal flora and cure the infection.

CDI can be catastrophic to patients and indeed to entire healthcare facilities if an outbreak occurs. To prevent CDI, follow these guidelines from the CDC:

- Immediately isolate patients with confirmed C. difficile infection and use contact precautions for the duration of diarrhea. Consider extending precautions beyond the duration of diarrhea and using presumptive contact precautions for patients with diarrhea pending confirmed C. difficile diagnosis.

- Educate healthcare personnel, patients, their families, and any visitors about C. difficile and help them maintain contact precautions.

- Follow proper handwashing techniques. Hand hygiene for C. difficile must include vigorous washing of hands with soap and water to mechanically remove spores. Alcohol-based hand rubs are not effective against C. difficile.

- Because C. difficile spores can survive on objects for long periods of time be sure to thoroughly clean and disinfect equipment and objects in the environment. Consider use of sodium hypochlorite (bleach)–containing agents or EPA-registered disinfectants with sporicidal claim for environmental cleaning.

- Enact a laboratory-based alert system for immediate notification of positive test results.